Sudoku Brawl (2013)

I’m really into the idea of taking solo, solve-at-your-own-pace puzzles and transforming them into competitive real-time games. Sudoku Brawl was my first attempt at this using Game Center as a core matching and communication service. I think it turned out well.

The original concept germinated from crossword puzzles. Jess and I cooperatively solve crosswords together before we go to bed (both of us playing on one screen). But what if we could “fight” each other – both trying to solve the same crossword on our own screens and racing to completion? I had the concept worked out fairly well, but the main problem implementing crossword games is sourcing puzzles. I couldn’t find good, free crossword puzzle databases anywhere, and I certainly don’t think I could program a crossword puzzle generator.

So I thought of other solo puzzles types, and landed on Sudoku. It turns out that Sudoku is kind of a perfect platform. The physical puzzle space fits well on the small phone screen. The puzzles can be solved in bite-sized time units, and unique boards can be quickly generated at run-time.

The Rules

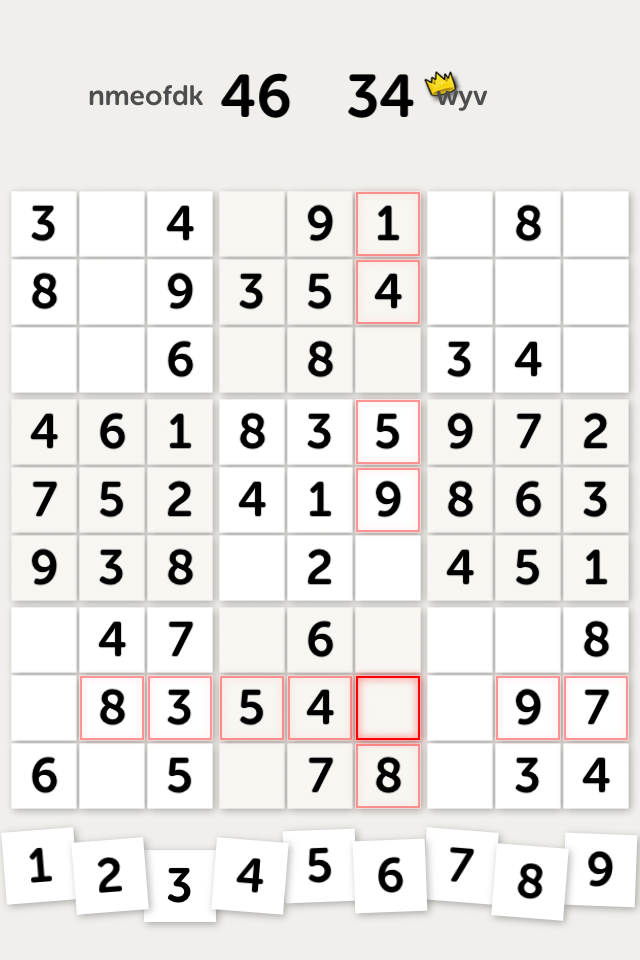

Sudoku Brawl gives each player (2-4) the same initial board layout. Players solve the puzzle using the same rules as standard Sudoku: one instance of each digit per row, column and block. When a player correctly identifies a cell, they score points and the cell is immediately revealed for all players (essentially claiming the cell for the guesser). The score is equal to the minimum of blank cells is the row, column or block – so in general, cells with more possible values score higher.

To prevent spam-guessing, a player is penalized in time for guessing incorrectly. The penalty is based on the square’s score value and a difficulty multiplier (so Evil puzzles will punish you with a higher time penalty than an Easy puzzle). During the time penalty you cannot guess cells, but you can still see the board. This opens certain strategies for guessing and planning future moves while in the penalty period.

I found everything to be a good balance. My mom is, objectively, a more experienced Sudoku player than me, but by adapting to the game mechanics I can keep the scoring in each match pretty neck-and-neck.

Dealing With Latency

It’s just a sad truth that any network game will have to deal with latency. In the case of Sudoku Brawl, it manifests itself with the problem of what to do when two players both guess a cell at the roughly the same time – who gets the points?

My initial thought was to have the players’ apps coordinate on who would be the central board authority. All moves would be routed to that player, who would then resolve conflicts and broadcast results. This was ok, but it still created a problem where someone who thought they had claimed a cell would end up not getting points for it. It was also going to be kind of a pain to write.

I ended up killing two birds with one stone by implementing the reservation rule: If a player has a cell highlighted (waiting for data input), it is reserved for them. Even if a second player correctly guesses that cell, it will still be hidden for the first player, who has an opportunity to enter a value until they highlight another cell. This means no one will be upset that they aren’t getting points for a cell they correctly identify.

This rule also simplified the protocol and allowed me to implement the entire game as peer-to-peer. All clients can maintain their state independently, and simply broadcast state-sync updates to all peers (scoring, penalties, etc). The only hard-sync state is the end, when one player has revealed all cells on their board. At this point, the game is over for everyone and scores are tallied.

In-App Purchases, or How This Game Will Not Make Me Rich

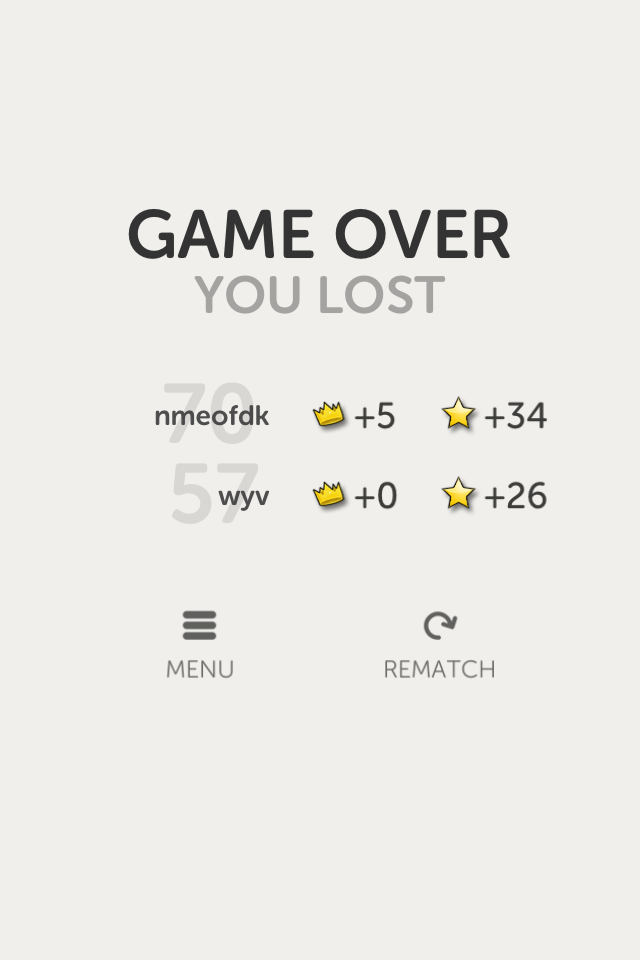

It’s pretty well known at this point that the freemium model is where you want to go with iOS apps these days. But the freemium model works best for games with consumable purchases that improve the gameplay. I couldn’t really hammer that model into Sudoku Brawl, and I didn’t want to compromise the experience by trying to shove in some sort of persistent need for credits, so I was left with the simple “unlock” in-app purchase model. Players initially get access to the easiest difficulty level, and can pay $0.99 to immediately unlock all other levels.

I included a reward cycle to augment that system. Players can unlock all skill levels for free by earning enough stars. I tried to pace it at around twenty victories to unlock each successive level (about an hour of gameplay). I figure if someone is a big enough fan to play 100 games, they deserve to the entire experience for free. Otherwise, I don’t think $0.99 is a huge barrier to those that want to play Evil puzzles right off the bat.

The bottom line is that there is no payment treadmill, so I’m not going to be pulling in thousands of dollars from hardcore players. If the game has good reception, I may consider rolling out another version that’s more conducive to consumable purchases – maybe making the game more combative (weapons, defense, special moves, etc). I’ll have to wait to see what the feedback is like.

Generating puzzles

One of the draws of Sudoku, for me, was the ability to dynamically create new puzzles without the need for some kind of puzzle database. To do this I had to code a puzzle generator that could create a variable-difficulty puzzle in about 1 second on the user’s phone.

It turns out this isn’t terribly difficult. I found a great paper that provided a really solid algorithmic base titled, “Sudoku Puzzles Generating: from Easy to Evil” ([sic on title] I can’t figure out the Author’s name; google it.) It turns out the real trick is writing a solver that can run in microsecond time, since that solver will need to run thousands of times while generating one puzzle.

Sudoku boards can be modeled in a really straightforward way (a 9×9 integer array plus a few arrays of metadata). It’s also really easy to transition back and forth from one state to the next given a “move” (digging a hole or filling one in with a guess). With these two advantages, I was able to write a solver that used a single board instance-worth of memory, and the depth-first search just tracked the move made to link from one state to the next. Without any dynamic memory nonsense, the solver ran blazingly fast.

To synchronize the boards in the peer-to-peer framework, I perform two synchronizing rounds between players: In the first round, all players broadcast their player names. All players sort the names alphabetically (deterministic), and the first name on the list is designated the board generator. The board generator then creates the board and broadcast the beginning state to all players. Since all Sudoku boards have unique solutions, the app runs the solver on the board to determine the end-state (in order to check guesses).

Game Center

Overall, I have mostly good things to say about Game Center. The API has a steeper learning curve than some other frameworks, but that’s just because it does a lot of complex things. In the end, when all the little quirks are understood, it comes together and plays well with the typical MVC-paradigm.

I really love not having to write any server code to do matching. Though I did end up writing a tiny little server widget that helped display the number of current players (since that’s not given by GC). Definitely an API to use in future apps.

App Store -- Link to Jess’s press release